* [PUBLISHER] upload files #175 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-19-symmetric-key-encryption.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #177 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-19-symmetric-key-encryptio.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #178 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #179 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #180 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #181 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #182 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #183 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #184 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #185 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #186 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #187 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 14. Secure Multiparty Computation.md * DELETE FILE : _posts/Lecture Notes/Modern Cryptography/2023-09-19-symmetric-key-encryption.md * DELETE FILE : _posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography/2023-09-18-symmetric-key-cryptography-2.md * [PUBLISHER] upload files #188 * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 14. Secure Multiparty Computation.md * DELETE FILE : _posts/Lecture Notes/Modern Cryptography/2023-09-19-symmetric-key-encryption.md * chore: remove files * [PUBLISHER] upload files #197 * PUSH NOTE : 수학 공부에 대한 고찰.md * PUSH NOTE : 09. Lp Functions.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-09.png * PUSH NOTE : 08. Comparison with the Riemann Integral.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-08.png * PUSH NOTE : 04. Measurable Functions.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-04.png * PUSH NOTE : 06. Convergence Theorems.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-06.png * PUSH NOTE : 07. Dominated Convergence Theorem.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-07.png * PUSH NOTE : 05. Lebesgue Integration.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-05.png * PUSH NOTE : 03. Measure Spaces.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-03.png * PUSH NOTE : 02. Construction of Measure.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-02.png * PUSH NOTE : 01. Algebra of Sets and Set Functions.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mt-01.png * PUSH NOTE : Rules of Inference with Coq.md * PUSH NOTE : 블로그 이주 이야기.md * PUSH NOTE : Secure IAM on AWS with Multi-Account Strategy.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : separation-by-product.png * PUSH NOTE : You and Your Research, Richard Hamming.md * PUSH NOTE : 10. Digital Signatures.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-10-dsig-security.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-10-schnorr-identification.png * PUSH NOTE : 9. Public Key Encryption.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-09-ss-pke.png * PUSH NOTE : 8. Number Theory.md * PUSH NOTE : 7. Key Exchange.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-07-dhke.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-07-dhke-mitm.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-07-merkle-puzzles.png * PUSH NOTE : 6. Hash Functions.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-06-merkle-damgard.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-06-davies-meyer.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-06-hmac.png * PUSH NOTE : 5. CCA-Security and Authenticated Encryption.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-05-ci.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-05-etm-mte.png * PUSH NOTE : 1. OTP, Stream Ciphers and PRGs.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-01-prg-game.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-01-ss.png * PUSH NOTE : 4. Message Authentication Codes.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-04-mac.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-04-mac-security.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-04-cbc-mac.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-04-ecbc-mac.png * PUSH NOTE : 3. Symmetric Key Encryption.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-03-ecb-encryption.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-03-cbc-encryption.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-03-ctr-encryption.png * PUSH NOTE : 2. PRFs, PRPs and Block Ciphers.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-02-block-cipher.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-02-feistel-network.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-02-des-round.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-02-DES.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-02-aes-128.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-02-2des-mitm.png * PUSH NOTE : 18. Bootstrapping & CKKS.md * PUSH NOTE : 17. BGV Scheme.md * PUSH NOTE : 16. The GMW Protocol.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-16-beaver-triple.png * PUSH NOTE : 15. Garbled Circuits.md * PUSH NOTE : 14. Secure Multiparty Computation.md * PUSH NOTE : 13. Sigma Protocols.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-13-sigma-protocol.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-13-okamoto.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-13-chaum-pedersen.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-13-gq-protocol.png * PUSH NOTE : 12. Zero-Knowledge Proofs (Introduction).md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : mc-12-id-protocol.png * PUSH NOTE : 11. Advanced Topics.md * PUSH NOTE : 0. Introduction.md * PUSH NOTE : 02. Symmetric Key Cryptography (1).md * PUSH NOTE : 09. Transport Layer Security.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-09-tls-handshake.png * PUSH NOTE : 08. Public Key Infrastructure.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-08-certificate-validation.png * PUSH NOTE : 07. Public Key Cryptography.md * PUSH NOTE : 06. RSA and ElGamal Encryption.md * PUSH NOTE : 05. Modular Arithmetic (2).md * PUSH NOTE : 03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2).md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-03-feistel-function.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-03-cfb-encryption.png * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-03-ofb-encryption.png * PUSH NOTE : 04. Modular Arithmetic (1).md * PUSH NOTE : 01. Security Introduction.md * PUSH ATTACHMENT : is-01-cryptosystem.png * PUSH NOTE : Search Time in Hash Tables.md * PUSH NOTE : 랜덤 PS일지 (1).md * chore: rearrange articles * feat: fix paths * feat: fix all broken links * feat: title font to palatino

13 KiB

share, toc, math, categories, path, tags, title, date, github_title, attachment

| share | toc | math | categories | path | tags | title | date | github_title | attachment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| true | true | true |

|

_posts/lecture-notes/modern-cryptography |

|

3. Symmetric Key Encryption | 2023-09-19 | 2023-09-19-symmetric-key-encryption |

|

CPA Security

Secret keys are hard to manage and it would be efficient if we could use the same key multiple times. So we need a stronger notion of security, that the adversary is given several ciphertexts under the same key but the scheme is still secure.

We strengthen the adversary's power, and assume that the adversary can obtain encryptions of any plaintext. This attack model is called chosen plaintext attack (CPA).

This notion can be formalized as a security game. The difference here is that we must guarantee security for multiple encryptions.

Definition. For a given cipher

\mathcal{E} = (E, D)defined over(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M}, \mathcal{C})and given an adversary\mathcal{A}, define experiments 0 and 1.Experiment

b.

- The challenger fixes a key

k \leftarrow \mathcal{K}.- The adversary submits a sequence of queries to the challenger: - The $i$-th query is a pair of messages

m _ {i, 0}, m _ {i, 1} \in \mathcal{M}of the same length.- The challenger computes

c _ i = E(k, m _ {i, b})and sendsc _ ito the adversary.- The adversary computes and outputs a bit

b' \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace.Let

W _ bbe the event that\mathcal{A}outputs1in experimentb. Then the CPA advantage with respect to $\mathcal{E}$ is defined as\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CPA}}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{E}] = \left\lvert \Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1] \right\lvertIf the CPA advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries

\mathcal{A}, then the cipher\mathcal{E}is semantically secure against chosen plaintext attack, or simply CPA secure.

The above security game is indeed a chosen plaintext attack since if the attacker sends two identical messages (m, m) as a query, it can surely obtain an encryption of m.

The assumption that the adversary can choose any message of its choice may seem too strong, but there are cases in the real world. Also, cryptographers use strong models to show proof of security even for strong attackers.

Deterministic Cipher is not CPA Secure

Suppose that E is deterministic. Then we can construct an adversary that breaks CPA security. For example, the adversary can send (m _ 0, m _ 1) and (m _ 0, m _ 2). Then if b = 0, the received ciphertext would be same, so the adversary can output 0 and win the CPA security game.

Therefore, for indistinguishability under chosen plaintext attack (IND-CPA), encryption must produce different outputs even for the same plaintext.

Another corollary is that PRPs are deterministic, so PRPs are not CPA secure.

Nonce-based Encryption

Since deterministic cipher is not CPA secure, we need non-deterministic encryption. There are two ways to construct such encryptions.

In probabilistic (randomized) encryption, encrypting the same message twice gives difference ciphertexts with high probability.

The second method is stateful encryption, where both algorithms E and D maintain some state that changes with each invocation of the algorithm. A typical example of stateful encryption is nonce-based encryption.

A nonce is a value that changes from message to message, such as a counter or a random value. Both encryption and decryption algorithm take the nonce as an additional input, so that the resulting ciphertext will be different for the same plaintext. Thus, it is natural that we require all nonces to be distinct.

The syntax for nonce-based encryption is c = E(k, m, n) where n \in \mathcal{N} is the nonce, and the algorithm E is required to be deterministic. Similarly, nonce-based decryption becomes m = D(k, c, n). The nonce that was used to encrypt m should be used for decrypting c.

We also formalize security for nonce-based encryption. It is basically the same as CPA security definition. The difference is that the adversary chooses a nonce for each query, with the constraint that they should be unique for every query.

Definition. For a given nonce-based cipher

\mathcal{E} = (E, D)defined over(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M}, \mathcal{C}, \mathcal{N})and given an adversary\mathcal{A}, define experiments 0 and 1.Experiment $b$.

- The challenger fixes a key

k \leftarrow \mathcal{K}.- The adversary submits a sequence of queries to the challenger. - The $i$-th query is a pair of messages

m _ {i, 0}, m _ {i, 1} \in \mathcal{M}of the same length, and a noncen _ i \in \mathcal{N} \setminus \left\lbrace n _ 1, \dots, n _ {i-1} \right\rbrace. - Nonces should be unique.- The challenger computes

c _ i = E(k, m _ {i, b}, n _ i)and sendsc _ ito the adversary.- The adversary computes and outputs a bit

b' \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace.Let

W _ bbe the event that\mathcal{A}outputs1in experimentb. Then the CPA advantage with respect to $\mathcal{E}$ is defined as\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{nCPA}}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{E}] = \left\lvert \Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1] \right\lvertIf the CPA advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries

\mathcal{A}, then the nonce-based cipher\mathcal{E}is semantically secure against chosen plaintext attack, or simply CPA secure.

Secure Construction from PRF

Suppose we want to construct a secure encryption scheme from a pseudorandom function. A simple approach would be to use E(k, m) = F(k, m), but this would result in deterministic encryption, which is not CPA-secure.

Therefore, we need randomized encryption. We achieve randomness by drawing a random value r \leftarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n and evaluate F(k, r) and then XOR it with the plaintext.

Here is the construction in detail.

Let

F : \mathcal{K} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^nbe a PRF.

- Encryption

E : \mathcal{K} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{2n}

- Sample

r \leftarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^nand returnc = (r, F(k, r) \oplus m).- Decryption

D : \mathcal{K} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{2n} \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n

- Extract

(r, s)fromcand outputm = F(k, r) \oplus s.

A few notes:

- Since we have randomized encryption,

Eis a one-to-many function.Dis a many-to-one function.

- The above construction maps

nbit messages to2nbit messages.- The ciphertext is

2times longer than the plaintext. - We call this the expansion ratio.

- The ciphertext is

- If the value

F(k, r)is duplicated in the above construction, then this scheme is insecure, just like in the one-time pad.- Thus the probability of duplication must be negligible.

Since the duplication probability is negligible, we have the following theorem.

Theorem. Let

Fbe a secure PRF. Then(E, D)in the above construction is CPA-secure.

Proof. Check the proof of Theorem 3.29.1

Notes on the Proof

There is a common proof template for constructions based on PRFs.

- Consider a hypothetical version of the construction, where the PRF is replaced by a truly random function.

- Argue that the adversary learns almost nothing. i.e, replacing with a random function only has a negligible effect on the adversary.

- Now that we have a random function, the remaining argument proceeds with probabilistic analysis, etc.

Modes of Operation

We learned how to encrypt a single block. How do we encrypt longer messages with a block cipher E : \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^s \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n?

There are many ways of processing multiple blocks, this is called the mode of operation.

Additional explanation available in Modes of Operations (Internet Security).

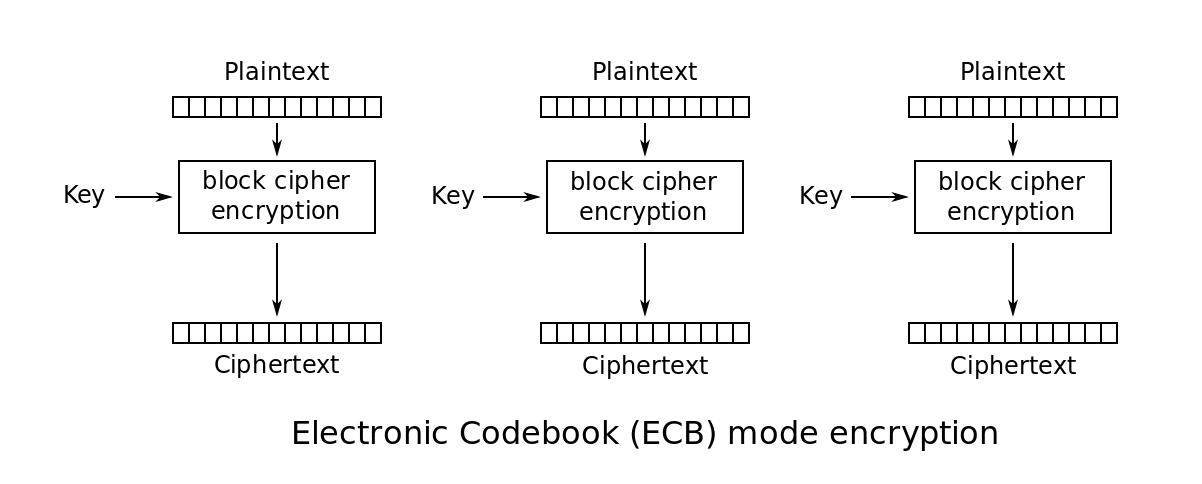

Electronic Codebook Mode (ECB)

- ECB mode encrypts each block with the same key.

- Blocks are independent of each other.

- ECB is deterministic, so not CPA-secure.

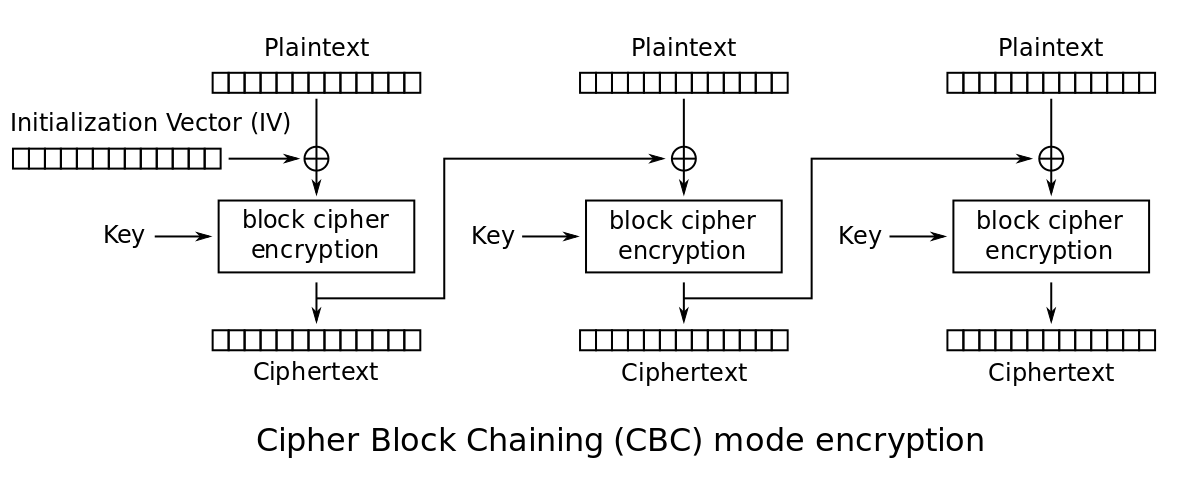

Ciphertext Block Chain Mode (CBC)

Let X = \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n and E : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow X be a PRP.

- In CBC mode, a random initial vector (IV) is chosen and outputs the ciphertext.

- Expansion ratio is

\frac{n+1}{n}wherenis the number of blocks. - If the message size is not a multiple of the block size, we need padding.

There is a security proof for CBC mode.

Theorem. Let

E : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow Xbe a secure PRP. Then CBC mode encryptionE : \mathcal{K} \times X^L \rightarrow X^{L+1}is CPA-secure for anyL > 0.For any $q$-query adversary

\mathcal{A}, there exists a PRP adversary\mathcal{B}such that\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CPA}}[\mathcal{A}, E] \leq 2 \cdot \mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{PRP}}[\mathcal{B}, E] + \frac{2q^2L^2}{\left\lvert X \right\lvert}.

Proof. See Theorem 5.4.2

From the above theorem, note that CBC is only secure as long as q^2L^2 \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert.

Also, CBC mode is not secure if the adversary can predict the IV of the next message. Proceed as follows:

- Query the challenger for an encryption of

m _ 0andm _ 1.- Receive

\mathrm{IV} _ 0, E(k, \mathrm{IV} _ 0 \oplus m _ 0)and\mathrm{IV} _ 1, E(k, \mathrm{IV} _ 1 \oplus m _ 1).- Predict the next IV as

\mathrm{IV} _ 2, and set the new query pair asm _ 0' = \mathrm{IV} _ 2 \oplus \mathrm{IV} _ 0 \oplus m _ 0, \quad m _ 1' = \mathrm{IV} _ 2 \oplus \mathrm{IV} _ 1 \oplus m _ 1and send it to the challenger. 4. In experiment

b, the adversary will receiveE(k, \mathrm{IV} _ b \oplus m _ b). Compare this with the result of the query from (2). The adversary wins with advantage1.

(More on this to be added)

Nonce-based CBC Mode

We can also use a unique nonce to generate the IV. Specifically,

\mathrm{IV} = E(k _ 1, n)

where k _ 1 is the new key and n is a nonce. The ciphertext starts with n instead of the \mathrm{IV}.

Note that if k _ 1 is the same as the key used for encrypting messages, then this scheme is insecure. See Exercise 5.14.2

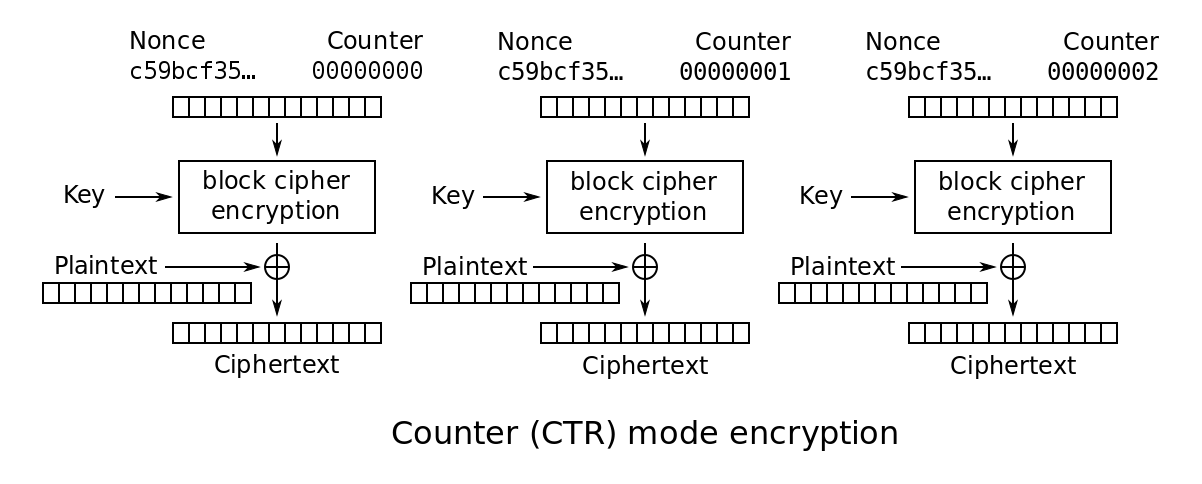

Counter Mode (CTR)

Let F : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow X be a secure PRF.

- CTR mode also chooses a random IV and increments the IV for every encrypted block.

- IVs should not be reused.

- CTR mode is parallelizable, so it is very efficient.

- If a part of the message changes, only that part has to be recalculated.

There is also a security proof for CTR mode.

Theorem. If

F : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow Xis a secure PRF, then CTR mode encryptionE : \mathcal{K} \times X^L \rightarrow X^{L+1}is CPA-secure.For any $q$-query adversary

\mathcal{A}againstE, there exists a PRF adversary\mathcal{B}such that\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CPA}}[\mathcal{A}, E] \leq 2\cdot\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{PRF}}[\mathcal{B}, F] + \frac{4q^2L}{\left\lvert X \right\lvert}.

Proof. Refer to Theorem 5.3.2

From the above theorem, we see that CTR mode is only secure for q^2L \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert. This is a better bound than CBC.

Nonce-based CTR Mode

We can also use a nonce and a counter to generate the IV. Since it is important to keep IVs distinct, set

\mathrm{IV} = (n, ctr) \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{64} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{64}

where ctr starts at 0 for every message and n \in \mathcal{N} is chosen randomly as a nonce.

Comparison of CTR and CBC

CTR is a lot better in general, but CBC is widely implemented.

| - | CBC | CTR |

|---|---|---|

| Primitive | PRP | PRF |

| Parallelizable | No | Yes |

| Security | q^2L^2 \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert |

q^2L \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert |

| Dummy Padding | Yes | No |

| 1-byte Message | 16 \times expansion |

No expansion |

- PRP is a PRF, so PRF is a weaker condition.

- The difference of

q^2L^2andq^2Lcomes from the probability that consecutive IVs overlap, and also the birthday paradox. - CBC needs dummy padding block, but this can be avoided using ciphertext stealing. (See Exercise 5.16.2 )

- CTR mode does not require padding by construction.